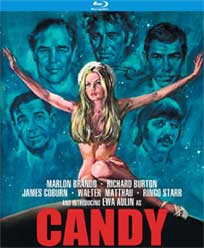

CANDY

(1968) Blu-ray

CANDY

(1968) Blu-rayDirector: Christian Marquand

Kino Lorber Studio Classics

CANDY

(1968) Blu-ray

CANDY

(1968) Blu-rayConsistently amusing—if too long—dirty joke, with a high-powered

all-star cast. Kino Lorber’s KL Studio Classics’s line

has released CANDY on Blu-ray, the 1968 American/French/Italian co-production

sex comedy (distributed by Cinerama Releasing here in the States) based on the

notorious Terry Southern/Mason Hoffenberg book, scripted by Buck Henry, directed

by Christian Marquand, and starring Richard Burton, Marlon Brando, Walter Matthau,

James Coburn, Ringo Starr, John Huston, Charles Aznavour, John Astin, Elsa Martinelli,

Sugar Ray Robinson, Anita Pallenberg, Enrico Maria Salerno, Umberto Orsini,

Florinda Bolkan, Marilu Tolo, Nicoletta Machiavelli, Lea Padovani, Joey Forman,

Fabian Dean, Buck Henry, and Miss Teen International 1966, Swedish bombshell

Ewa Aulin, in the title role. Critically dismissed when first released at the

very end of 1968, CANDY nevertheless sold a ton of theater tickets to a general

public curious to see big stars like Burton and Brando and Matthau cavorting

around in what audiences just hoped would be a “dirty”

movie. And on that gewgaw level, CANDY works pretty well: it may drag at times,

but the laughs are always there...even if the fuzzy, scattershot satire was

already stale by ‘69. Kino has come up with a sparkling new 2K restoration

for this Blu 1080p release, along with a few extras, including a fun new interview

with Buck Henry, an unintentionally funny new interview with someone named Kim

Morgan, and some original radio spots and a trailer.

A cosmic amalgamation of crystals and lights amid the stars descends to the

ocean beach and then the American Southwest desert, transforming itself into

knee-weakening blonde, wide-eyed, pouting Candy (Ewa Aulin, DEATH SMILES ON

A MURDERER, I AM WHAT I AM). Just as suddenly, Candy is now a vacant, ready-to-please

high schooler at Rolling Fields Center High School, where her father, overly

tense prig T.M. Christian (John Astin, TV's THE ADDAMS FAMILY, GET TO KNOW YOUR

RABBIT), teaches social sciences while vigorously suppressing incestuous stirrings

for his nubile, micro mini-dressed daughter. Enter McPhisto (Richard Burton,

STAIRCASE, BLUEBEARD), superstar poet and degenerate drunk, whose visit to Rolling

Fields includes a stirringly hammy rendition of his latest lust-filled opus,

and an invitation for Candy to ride home in his limo, piloted by seen-it-all

driver, Zero (Sugar Ray Robinson, THE DETECTIVE, THE TODD KILLINGS). Too drunk

to score with Candy (“My huge, overpowering need!”), McPhisto

nails one of her dolls in Daddy’s basement playroom as he spurs on poor

Mexican gardener Emmanuel (Ringo Starr, THE MAGIC CHRISTIAN, CAVEMAN) to deflower

Candy on the pool table—an act of defilement that enrages her father when

they’re caught...and which delights his pervy, lecherous twin, Uncle Jack

(Astin in a dual role). Deciding to send Candy to school in New York, the Christian

family barely escapes death at the hands of Emmanuel’s biker gang sisters

(“Ladies, a bit of flagellation is okay, but this is going too far,”),

before they’re rescued by General Smight (Walter Matthau, THE FORTUNE

COOKIE) whose perpetually flying paratroop ship has briefly landed at the airport

for refueling. T.M., however, suffers a brain injury thanks to one of the bikers,

and Candy will do anything if General Smight—who’s been

in the air without a woman for six years—will help. Alas, the General’s

prolonged abstinence induces premature bail-out when he corners a nude Candy

in the cockpit, so cut to The New York Neuro-Homeopathic Center, where superstar

brain surgeon Dr A. B. Krankeit (James Coburn, IN LIKE FLINT, HARD TIMES), performing

live for the cocktail crowd, is going to fix Daddy with a sub-cranial medulla

oblongotomy (the movie poster-like surgery announcement states, “No one

will be seated after the first incision,”). A wild post-op party ensues,

with both Uncle Jack and the good doctor trying to nail Candy, before she escapes

the hospital and makes her way out onto the even crazier streets of “Fun

City.” There she meets fanny-pinching gangster, the “Big Guy”

(Umberto Orsini, THE DAMNED, EMMANUELLE II), self-absorbed lunatic cinema

verite director Jonathan J. John (Enrico Maria Salerno, THE BIRD WITH THE

CRYSTAL PLUMAGE, EXECUTION SQUAD), and a human fly hunchback (Charles Aznavour,

THE ADVENTURERS, THE GAMES), before two instantly violent cops (“Let’s

get ready to beat somebody to a pulp!”) bust her (Joey Foreman, THE NUDE

BOMB and Fabian Dean, THE BAREFOOT EXECUTIVE). Candy escapes their lewd clutches

only to be introduced to seven levels of sexual enlightenment courtesy of mobile

semi-tractor trailer guru Grindl (Marlon Brando, REFLECTIONS IN A GOLDEN EYE,

THE NIGHTCOMERS)...before her true awakening comes.

Originally published in 1958 for French “smut” peddler Maurice Girodias

and his Olympia Press, Candy went from being a whispered-about cult

phenomenon here in the States, to full-blown mainstream commercial success when

authors Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg had G.P. Putnam’s Sons re-publish

the novel under their real names in 1962; the book went on to become the second

best-selling fiction book of 1963 in the United States. Had a movie adaptation

of Candy somehow been produced that year, in spite of the still-enforced

but rapidly-crumbling Production Code, it’s arguable whether CANDY would

have had a bigger impact with critics and audiences still relatively unexposed

to even mildly suggestive sexual themes (certainly it would have been scrubbed

clean, as was Kubrick’s LOLITA the year before). By the time CANDY finally

did wind up on screens at the very end of 1968, however, the world’s movie

houses were already convulsing with heretofore forbidden subject matter and

nudity. So the appearance in ‘68 of an all-star adaptation of a once-scandalous

10-year-old book ironically carried with it a hidden patina of respectability

that muted the movie’s intended outrageousness. After all, the pubic (despite

critics’ constant assertions to the contrary) wasn’t stupid—they

knew that despite the rapidly-changing times on American movie screens, huge

stars like Brando and Burton and Matthau wouldn’t be doing anything too

naughty in CANDY, lest their big money-earning reputations be suddenly downgraded

to the lower levels of exploitation cinema.

And if CANDY’s erotic charge was muted either by savvy audience expectations

or outright design to keep the movie barely within the borders of acceptability

(as scripter Buck Henry freely admits on this disc’s bonus interview),

its intended satire was a victim of thorough familiarity. CANDY’s targeting

of incestuous bourgeoisie fathers (LORD LOVE A DUCK peeked at that a good two

years earlier...even REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE briefly touched on it), boozy, self-important

intellectual celebrities, narcissistic, murderous doctors (TV covered that a

few times on BEN CASEY and DR. KILDARE), impotent war mongers (DR. STRANGELOVE,

clearly), oversexed “foreign” revolutionaries (aren’t they

all in the movies?), and phony, oversexed religious charlatans (you could stretch

that one right to ELMER GANTRY), were already familiar butts of pop culture

jokes in ‘68. There’s nothing in CANDY that couldn’t have

been found at that time in Playboy cartoons...or even a MAD

magazine. Critics at the time correctly noted CANDY’s tired, diffused

satirizing (while grumpily ignoring the fact that old jokes can still get laughs

if told right), but audiences took to it, making relatively low-budgeted CANDY—despite

modern critics parroting the same wrong information—one of 1968’s

most successful pictures at the U.S. box office, coming in 18th for the year,

with eventually over $16 million in ticket sales (if CANDY “lost”

money for anyone on returned rentals of $8 million just from the U.S. release

alone—not counting its worldwide net—it was no doubt due to those

mysterious accounting “tricks” endemic in the moviemaking biz. Someone

made money on that gross).

So that just leaves the sex and the nudity and the performances and the jokes.

Forget trying to find deep meaning in CANDY; this is a shallow, smutty, picaresque

lark, haphazardly designed to titillate and briefly amuse...and it comes off

not too much the worse for wear, aiming that low (if you think CANDY

is saying something new or brave or feminist about “men are ridiculous

sexual creatures,” well...who the hell didn’t know that already

by ’69? Go back to Shakespeare, just for a convenient start). Assembled

in a remarkably similar fashion to the previous year’s all-star comedy

romp, the James Bond spoof, CASINO ROYALE (which Southern and director John

Huston worked on), CANDY plays to the viewer just as scripter Buck Henry describes

its actual physical production. Big name actors were sought to guarantee box

office on an admittedly slim premise (he states the book was funny, but lacked

big, memorable scenes needed for a movie). Once they were signed, scenes were

hastily constructed to their liking, around their limited schedules, regardless

of how well those scenes fit into an overall aesthetic scheme (Henry states

in the disc’s interview that at one point he was writing only 11 pages

ahead of the actual shooting). For critics and viewers unpleasantly surprised

by the movie’s overall schizophrenic vibe...who wouldn’t

suspect that a movie based on a co-written book (chapters were alternated between

the two authors, who were in separate countries), adapted by an American scripter

(after Southern’s script was tossed out) for French, Italian and American

producers, with a Frenchman directing an international cast, might

have problems of sustained, unified tone?

And just like CASINO ROYALE, you can bitch about the frequent lack of proper—or

even basic—filmmaking technique in CANDY, such as understandable scripting,

direction, and editing (and you’d be perfectly right to do so, should

your mood dictate)...while at the same time just grooving along with the movie

and getting what laughs you can out of the mess. CANDY’s biggest problem

was CASINO ROYALE’s, as well—it’s way too long. It’s

certainly not a hard or fast rule, but full-on comedy on the screen, except

on rare occasions, or if its balanced by dramatic elements, can often begin

to wilt after 90 to a 100 minutes, and at 124 minutes, CANDY is just too much

candy. Scenes that go on and on and on (it’s too bad that Coburn’s

operation and post-op orgy scenes are the chief victims; the extended, pointless

Fellini motorcycle chase fails, and Brando’s funny sequence goes just

beyond its successful reach) would have received twice the laughs and impact

if the scissors had come out and liberal cuts were made (and scenes that just

plain stink, like Umberto Orsini’s “Big Guy” gangster...or

almost all of Matthau’s embarrassing segment, could have been excised

completely).

What saves CANDY, however, is that an amusing joke or line reading somehow always

pops up right when we’re tempted to check how much time is remaining on

the disc. And that’s all a comedy needs to be successful: do we laugh

at the material more than we silently observe? CANDY’s nominally biggest

stars, Burton and Brando, anchor the movie’s opening and closing (Astin

actually does but, excellent as he is here, he doesn’t elicit the expectations

and anticipation in us that those two giants do), and they do what big stars

should in such a project: deliver the goods for their hefty paychecks. Burton’s

opening segment as a demented Dylan Thomas-ish superstar poet is the movie’s

highlight (which necessarily dooms CANDY to a downward trajectory). It’s

beautifully written by Henry (that poem from the hilariously monikered collection,

Forests of Flesh, had me on the floor with “Life which burned

and bled in the triumph of my dream dim days”), nicely directed by Marquand

(he gets a laugh just quick-panning the camera back to Candy, framed in a rose-covered

arbor like an impossibly hot Madonna), and brilliantly acted, frankly, by Burton

(lapsing into a commercial for his own book sales, even to the point of repeating

the address to send a check, may be one of the best-timed pieces the actor ever

committed to the screen). Burton lapping up liquor off a glass-bottomed limo

as the camera shoots up at him, is often cited with utter disdain by disgusted

critics, but it’s a paralyzingly funny moment, one that shows Burton completely

loose and unhinged (and as we’d like to imagine that glorious hellraiser

might have acted, just once, in his private moments). Just the sight of Burton’s

Byronically teased-out hair perpetually blowing in an unseen, private breeze,

his preening, ravaged face a mask of immensely satisfied self-adulation, is

worth the price of the whole movie.

As for Brando, increasingly considered box office poison throughout the 1960s,

I find it hard to believe he was the sole reason, as some suggest, that CANDY

was financed (yes, he was close friends with director Marquand...but friendship

doesn’t get producers to sign checks: a source novel notorious all over

the world for its sexual content, and a gaggle of other famous stars signed

up for a naughty farce, does). Seeing him here, in a performance he himself

described as his worst on-screen, it takes a minute or two for us to get past

the outrageousness of witnessing America’s greatest screen actor playing

a badly-accented guru, complete with dye job and flowing wig (a wig he’s

brave enough to let keep slipping). However, once we see how committed he is

to the broad farce, and how skilled he is at the poor jokes (“‘Gosh!’

‘Gosh’ isn’t the half of it!”), it’s a marvelous

crack-up, made all the more fun because of Brando’s own (and hated) self-serious

reputation. And Marquand rises to the occasion, as well, shooting the sequence

with a lot of verve, getting big laughs when he stages a montage of various

groupings of Brando’s disembodied head among assorted feet and hands—his

and Candy’s—as Brando has Kama Sutra sex with her, telling the story

of The Pig and the Flower (Brando’s guru also offers up a bit

of Eastern wisdom about a centipede that can’t tap dance...but then admits

the analogy loses something in the translation).

What lies between these two standouts, is a mixed bag. John Astin, certainly

most known at this time (at least in the States) for re-runs of TV’s THE

ADDAMS FAMILY, gets the movie’s biggest part—an odd choice considering

how lesser his movie star power was compared to his co-stars (I’ve always

suspected everyone hoped to draw in Peter Sellers for one of his patented dual

roles, to no avail, and Astin was a last-ditch choice). Astin’s quite

funny, though, particularly as blase pervert Uncle Jack, matched well by the

amoral chic of his beautiful wife, Elsa Martinelli (who regrettably has little

to do here). Coburn probably didn’t know at this time that he had already

peaked at the box office; his Derek Flint movies were his biggest claim to fame

before he overexposed himself with box office misfires like WHAT DID YOU DO

IN THE WAR, DADDY?, DEAD HEAT ON A MERRY-GO-ROUND, WATERHOLE NO. 3, THE PRESIDENT’S

ANALYST, DUFFY, and HARD CONTRACT, all bombing in a span of just three short

years. He’s always great delivering big, bombastic line readings with

weird spins of emphasis and hidden comedy (with his middle finger inserted entirely

into Astin’s brain, he yells, “My left index finger is now fully

three inches inside the patient’s head. A hiccup would put a dent in the

patient’s speech center that would leave him not only incapable of pronouncing

the letters L, R, D, Y and F, but make him absolutely incapable of digit-dialing!”).

But the length of the scene defeats the performance in the end (he recovers

when he starts trading insults with a hilariously grave John Huston, too briefly

seen here). Critics seem to universally hate the Charles Aznavour hunchback

scene, but I laugh every time he jumps around like a human fly, crawling on

the walls and ceilings; it’s weirdly-constructed, surreal slapstick. I’m

not too familiar with Enrico Maria Salerno, but he scores one of the best moments

in CANDY, as the self-obsessed cinema verite director who wants to

document hundreds of people simply saying, “No,” particularly himself,

because it’s a “part of life” (there’s real manic comedy

energy here with Salerno; pity his sequence was so short).

The critics are right, though, about Ringo Starr’s Emmanuel: the less

said, the better—not because of any perceived racism with the character

(if you’re offended by anything in CANDY, you need to seriously lighten

up: the beginning of the end of political correctness is hopefully on the way)...but

because he’s simply, excruciatingly unfunny here. If you look

at CANDY’s U.S. one-sheet poster, you’ll see 1968’s biggest

box office star among this cast, Walter Matthau, right at the top of the pyramid

of star images (he had steadily been gaining a following, before scoring the

4th biggest movie of 1968 that winter and spring: THE ODD COUPLE). Unfortunately,

his segment in CANDY is the least effective, being too similar to the comedy

in DR. STRANGELOVE, and delivered in a surprisingly awkward, ungainly manner

by an unconvinced Matthau; his simulated premature ejaculation is probably the

actor’s lowest career point (I’m betting he’s one of the actors

Henry alludes to in the doc, who didn’t really want to be here). As for

the star of CANDY, Ewa Aulin, it isn’t enough to just give her credit

for being not only stunningly beautiful, but sexy as hell (two entirely different

things), despite her voice being dubbed. She’s actually quite funny as

the perpetually flummoxed Candy; she has a reaction shot to Matthau’s

twisted reasoning that’s a masterstroke of comedic timing (or just spot-on

editing). Nobody seems to understand why the script has Candy coming to Earth

from space, but looking at Aulin, looking at that body and face, and seeing

her believably perplexed look as she charges around the sets driving every character

mad with insane desire, then the only explanation for her otherworldly appeal

is that she must be an alien: real women like her just don’t

exist in our realm, the movie seems to say...and we believe it seeing Aulin.

It’s a shame that she couldn’t do more comedy (she was equally accomplished

in the cult favorite, START THE REVOLUTION WITHOUT ME, before she wandered off

into Italian giallos, eventually quitting the business altogether).

If CANDY is going to work on the most basic level, we have to buy that the title

character would indeed drive every man she meets instantly, insanely into lust.

Aulin pulls that off (no mean feat—you think Meryl Streep or Bette Davis

could do that?), innocently keeping the dirt in CANDY amusing and light. Without

her, Brando and Burton and the rest of the cast would be even more at sea than

they are here in this chaotic but undeniably entertaining sex farce.

The 2K restoration, MPEG-4 AVC 1080p HD 1.85:1 widescreen transfer for CANDY is quite a step up from the old 2001 Anchor Bay limited pink tin edition of the movie. Grain structure is far more tight, and colors now are quite bright and pop-y, compared to the previous muddy, mushy transfer. Fine image detail is greatly improved, as well; blacks are much more stable, and contrast sharper. The DTS-HD Master split mono 2.0 English-only audio track is unexciting but solidly re-recorded, with composer Dave Grusin's score (with the help of The Byrds and Steppenwolf) coming over full and uncompressed. No subtitles available. Two new interviews are included as extras. "Bitter Sweet with Buck Henry" (16:48) finds the writer/director in sharp form reminiscing about CANDY's production. He dismisses feminist P.C. concerns about movies featuring beautiful women (how refreshing to hear him simply tell the truth about Aulin: "just this incredibly hot, toothsome babe from the magical islands of Scandinavia"). He's also open about quoting more noted, respectable authors into his work, to make himself seem smarter than he apparently thinks he is (you've gotta be smart to know the quotes), and he has some fun stories about the actors working in the movie. He claims he's only seen CANDY once, in a screening room right after the movie was finished, and the reaction was so depressing he feared he'd never write for the movies again. A solid interview from a well-spoken pro. "Sugar Rush with Kim Morgan" (9:36), on the other hand, may be one of the funniest ramblings I've heard in some time about pop culture and movie criticism. I watched it twice, now, and I still don't know what the hell she's talking about...and neither does she, as she freely admits: "[CANDY] has this mysterious essence to it that I can't quite pull out of exactly what it is, sort of the darkness and the light." Oh-kay. For some reason, Miss Morgan seems to be in a constant state of confusion—not unlike the title character, come to think of it—as to what CANDY is, or what it says, or what it means...which frankly doesn't bode well for someone who calls herself a "film critic" ("It's hard to describe, it's hard to articulate simply,"). As a final summing up, we get this rather remarkable switchback in equivocating movie criticism: "There's all these difficult things about the movie that whether or not you find it good—and I don't even think that's the right way to look at it; 'Is this a good movie?'—that don't really matter. Just watch it for the experience. It's complex, it's hard to distill into one thing," Jesus Christ. Also included are two original radio spots, and an original trailer. (Paul Mavis)