ROSEMARY’S

BABY (1968)

ROSEMARY’S

BABY (1968)Director: Roman Polanski

The Criterion Collection

ROSEMARY’S

BABY (1968)

ROSEMARY’S

BABY (1968)The birth of ROSEMARY’S BABY may not have been a happy event, but Criterion’s new Blu-Ray edition is a very special occasion with a beautiful new transfer and new special features.

Housewife Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow, ALICE) and her actor husband Guy (John Cassavetes, THE INCUBUS) find the slightly pricey apartment of their dreams in the rambling Gothic revival Bramford apartment building whose clientele once included Victorian cannibals, orgy enthusiasts, baby killers and Satanists (according to Rosemary’s knowledgeable friend Hutch [Maurice Evans, PLANET OF THE APES]). As with many of the apartments in the buildings, the Woodhouses’ apartment is a smaller segment partitioned off from a larger one, and at night the young couple hears strange chanting coming from behind their bedroom wall. No sooner has Rosemary made a friend in Terry (INVASION OF THE BEE GIRLS’ Victoria Vetri, billed as Angela Dorian since Rosemary tells her she looks like Vetri) – an ex-junkie taken in by the Woodhouses’ kindly neighbors the Castevets – then the girl winds up splattered on the sidewalk (an apparent suicide).

The

Castevets – nosy Minnie (Ruth Gordon, HAROLD AND MAUDE) and sophisticated

Roman (Sidney Blackmer, HIGH SOCIETY) – soon embroil themselves in the

personal lives of Rosemary and Guy. Roman regales Guy with tales of his worldwide

travels with a theatrical troupe in the earlier half of the century and Minnie

gifts Rosemary with the same charm – containing Tannis Root (or Devil’s

Pepper) – that had once been worn by Terry. Guy’s luck changes when

the lead role in a play he auditioned for inexplicably goes blind, and things

are looking up with the potential for a TV series lead. With his future success

seemingly guaranteed, Guy thinks it’s time he and Rosemary try for their

first baby. A chocolate mousse provided by Minnie (who calls it a “mouse”)

makes Rosemary sick and drowsy on the couple’s planned night of passion,

and the young woman dreams of copulating with the devil under the eyes of a

coven that includes Roman, Minnie, Guy and several of her neighbors. When Rosemary

announces that she is pregnant, Roman fixes her up with high-end Dr. Sapirstein

(Ralph Bellamy, HIS GIRL FRIDAY) who favors natural herbs over vitamins.

The

Castevets – nosy Minnie (Ruth Gordon, HAROLD AND MAUDE) and sophisticated

Roman (Sidney Blackmer, HIGH SOCIETY) – soon embroil themselves in the

personal lives of Rosemary and Guy. Roman regales Guy with tales of his worldwide

travels with a theatrical troupe in the earlier half of the century and Minnie

gifts Rosemary with the same charm – containing Tannis Root (or Devil’s

Pepper) – that had once been worn by Terry. Guy’s luck changes when

the lead role in a play he auditioned for inexplicably goes blind, and things

are looking up with the potential for a TV series lead. With his future success

seemingly guaranteed, Guy thinks it’s time he and Rosemary try for their

first baby. A chocolate mousse provided by Minnie (who calls it a “mouse”)

makes Rosemary sick and drowsy on the couple’s planned night of passion,

and the young woman dreams of copulating with the devil under the eyes of a

coven that includes Roman, Minnie, Guy and several of her neighbors. When Rosemary

announces that she is pregnant, Roman fixes her up with high-end Dr. Sapirstein

(Ralph Bellamy, HIS GIRL FRIDAY) who favors natural herbs over vitamins.

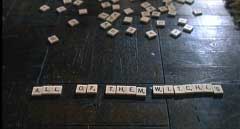

Instead of a glow, pregnant Rosemary takes on an unhealthy pallor and loses rather than gains weight. When Hutch becomes suspicious and does some investigating, he falls into a sudden coma before he can tell Rosemary and dies. He does, however, leave behind a book titled All of Them Witches with the cryptic clue “The name is an anagram.” One of the witches described in the book is former Bramford resident Adrian Marcato, a Satanist who was killed in the building. As the months pass and her health deteriorates Rosemary suspects that the residents of the building are Satanists and that they have special plans for her baby.

Times

have certainly changed, and it’s even less believable now than it was

then that an unemployed actor and a housewife could afford an apartment that

size – especially considering the residents of the Bramford building’s

actual location The Dakota (ranging from Boris Karloff, Judy Garland, Leonard

Bernstein, and Lilian Gish to Yoko Ono, Connie Chung and Maury Povich, Joe Namath,

and John Madden among others since the earlier half of last century) –

but Roman Polanski’s ROSEMARY’S BABY may be one of the most influential

American horror films of all time. People know the plot without ever having

seen the film or read the Ira Levin’s source novel (some may even be convinced

that they have seen it when they have not). Contemporary viewers of the film

will have absolutely no trouble predicting every plot turn, but that is more

the result of the novel and film’s extensive influence on subsequent literature,

film and television of various genres. The film’s success also certainly

made the more graphic THE EXORCIST and THE OMEN more viable, as well as more

derivative works like Fred Mustard Stewart’s novel THE MEPHISTO WALTZ

(and Paul Wendkos’ 1971 film version), Jeffrey Konvitz’s novel THE

SENTINEL (and its Michael Winner film adaptation), and many other scenarios

where young people stumble upon too-good-to-be-true opportunities from Ken Eulo’s

THE BROWNSTONE, Andrew Neiderman’s novel (and Taylor Hackford‘s

film of) THE DEVIL’S ADVOCATE to, more recently, ABC’s hokey-looking

(and likely soon to be cancelled) 666 PARK AVENUE.

Times

have certainly changed, and it’s even less believable now than it was

then that an unemployed actor and a housewife could afford an apartment that

size – especially considering the residents of the Bramford building’s

actual location The Dakota (ranging from Boris Karloff, Judy Garland, Leonard

Bernstein, and Lilian Gish to Yoko Ono, Connie Chung and Maury Povich, Joe Namath,

and John Madden among others since the earlier half of last century) –

but Roman Polanski’s ROSEMARY’S BABY may be one of the most influential

American horror films of all time. People know the plot without ever having

seen the film or read the Ira Levin’s source novel (some may even be convinced

that they have seen it when they have not). Contemporary viewers of the film

will have absolutely no trouble predicting every plot turn, but that is more

the result of the novel and film’s extensive influence on subsequent literature,

film and television of various genres. The film’s success also certainly

made the more graphic THE EXORCIST and THE OMEN more viable, as well as more

derivative works like Fred Mustard Stewart’s novel THE MEPHISTO WALTZ

(and Paul Wendkos’ 1971 film version), Jeffrey Konvitz’s novel THE

SENTINEL (and its Michael Winner film adaptation), and many other scenarios

where young people stumble upon too-good-to-be-true opportunities from Ken Eulo’s

THE BROWNSTONE, Andrew Neiderman’s novel (and Taylor Hackford‘s

film of) THE DEVIL’S ADVOCATE to, more recently, ABC’s hokey-looking

(and likely soon to be cancelled) 666 PARK AVENUE.

The film also made its mark on international exploitation: for instance, Australia’s ALISON’S BIRTHDAY, Spain’s BLACK CANDLES, SATAN’S BLOOD, and THE DRACULA SAGA, and particularly Italy with Mario Siciliano’s EVIL EYE, Sergio Martino’s ALL THE COLORS OF THE DARK, and the REPULSION-esque PERFUME OF THE LADY IN BLACK (even Lucio Fulci’s late EXORCIST-ripoff MANHATTAN BABY had a benevolent character named Adrian Marcato for no particular reason). The Sabbat in which Rosemary copulates with the devil was recreated virtually shot-for-shot in Michele Soavi’s THE CHURCH (1989) – right down to the whispered chant (with GOBLIN musician Fabio Pignatelli’s “Possession” theme a slicker version of Komeda’s underscore) but without visits from Jackie Kennedy and the pope – and Levin’s scenario was also a definite influence on Soavi’s THE SECT (1991). Even Polanski’s arguably superior THE TENANT (based on the novel by Roland Topor) cannot help but be compared to the earlier film, whether or not Polanski intended it (although Polanski himself in drag during the finale looks more than a bit like Ruth Gordon’s Minnie here). Polanski would return to Satanism with the more fantastic THE NINTH GATE (based on part of Arturo Pérez-Reverte’s novel THE CLUB DUMAS), but comparisons are inevitable.

The

novel was also undoubtedly an influence on Levin’s own half-hearted 1991

thriller SLIVER, which also includes a desirable property with a bad reputation

(a laundry list of tragedies is rattled off by the protagonist’s ex-husband

early on). The 1992 film adaptation – mounted as an erotic thriller scripted

by Joe Eszterhas and starring Sharon Stone to cash-in on their previous collaboration

BASIC INSTINCT – was produced by Robert Evans, who started as head of

production at Paramount in 1967 and enticed Polanski into directing ROSEMARY’S

BABY and would later produce CHINATOWN, also featured production design by Paul

Sylbert (twin brother of ROSEMARY’S BABY production designer Richard Sylbert),

and executive produced by Howard Koch Jr. (who had served as dialogue coach

on the Polanski film).

The

novel was also undoubtedly an influence on Levin’s own half-hearted 1991

thriller SLIVER, which also includes a desirable property with a bad reputation

(a laundry list of tragedies is rattled off by the protagonist’s ex-husband

early on). The 1992 film adaptation – mounted as an erotic thriller scripted

by Joe Eszterhas and starring Sharon Stone to cash-in on their previous collaboration

BASIC INSTINCT – was produced by Robert Evans, who started as head of

production at Paramount in 1967 and enticed Polanski into directing ROSEMARY’S

BABY and would later produce CHINATOWN, also featured production design by Paul

Sylbert (twin brother of ROSEMARY’S BABY production designer Richard Sylbert),

and executive produced by Howard Koch Jr. (who had served as dialogue coach

on the Polanski film).

In the new Blu-Ray’s documentary, Polanski mentions that Levin’s novel needed only to be converted into a shooting script – Levin once described the film as "the single most faithful adaptation of a novel ever to come out of Hollywood” – while Farrow believes that the resulting film would have been very different had it been directed by anyone else; and it is Polanski’s performance-centered direction that anchors Farrow’s flightiness into focused neurosis and keeps fellow filmmaker Cassavetes’ acting ticks and comic asides seeming natural rather than stealing focus. Whereas several of the aforementioned films and novels portray their villains as seductively evil, ROSEMARY’S BABY’s Satanists are a bunch of prying kooks, so much so that it is difficult to tell if their eccentric behavior is an act (THE SENTINEL also tried this, but went far overboard that the heroine had to be stupid rather than too polite to withstand her neighbors’ behavior). It is also to Polanski’s credit that the varying performance styles of Gordon, Blackmer, and Bellamy, as well as Patsy Kelly – as Minnie’s equally cracked neighbor – and TV sitcom regular comic sadsack Phil Leeds never overwhelm the scenes (particularly the important final one). Look out for a young Charles Grodin as Rosemary’s original doctor, D’Urville Martin (who would go from films like this and GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DINNER to Blaxploitation in the 1970s) as the apartment’s elevator man, and Elisha Cook Jr. as the building’s rental agent (Cook was no stranger to horror with appearances in HOUSE ON HAUNTED HILL and Roger Corman’s THE HAUNTED PALACE, but he would later garner horror roles in TV’s THE NIGHT STALKER, MESSIAH OF EVIL and BLACULA following Polanski’s film). Producer William Castle has a cameo late in the film (Corman’s cameo in Joe Dante’s THE HOWLING seems like a direct copy of this scene) and an uncredited Tony Curtis has a cameo as the phone voice of Guy’s acting rival. Composer Krzysztof Komeda had scored all of Polanski’s previous work – apart from REPULSION due to union reasons – most memorably KNIFE IN THE WATER and THE FEARLESS VAMPIRE KILLERS. His memorable lullaby main theme – voiced by actress Farrow – also proved to be as influential in horror films (as well as Ennio Morricone’s giallo scores) as Latin choirs after THE OMEN. Editor Sam O’Steen, who would edit all of Polanski’s subsequent films until his death in 2000, would helm the TV sequel LOOK WHAT’S HAPPENED TO ROSEMARY’S BABY, which retained Gordon as Minnie but recast Patty Duke as Rosemary, Sam Maharis as Guy, Ray Milland as Roman, and Stephen McHattie as Rosemary’s grown son. Ira Levin would pen his own novel sequel SON OF ROSEMARY in 1997 (which Criterion’s new release covers with the inclusion of a 1997 radio interview between the author and Leonard Lopate [19:21]).

Typical

of a Paramount-licensed release, Criterion’s dual-layer Blu-Ray is coded

for Region A playback only, and it is currently the only Blu-Ray edition in

the world (but can a Paramount Region B release or two be far behind now that

Criterion has done the work on the master?). Due to the film’s pedigree,

ROSEMARY’S BABY has been fairly well-treated on DVD by Paramount (a company

that tended to dump its genre releases onto barebones disc with little digital

clean-up, prior to sublicensing several of their titles to Olive Films who continue

to dump their titles onto DVD with little restoration or extras); as such, Criterion’s

1080p MPEG-4 AVC encoding features similar 1.85:1 framing and colors to Paramount’s

2003 Region 1 NTSC DVD edition, but the new HD transfer is sharper, more detailed,

and almost looks like it could have been shot yesterday (although any recent

film attempting to capture the look of the era would probably try to degrade

the image to reflect the condition of how many of these older films look now

without restoration). Farciot Eduoart’s (VERTIGO) process shots during

Rosemary’s nightmares have always looked artificial, although some subtler

looking ones are also more obvious (notably the elevator scenes). The audio

is encoded in uncompressed LPCM single-channel mono; it may be subjective, but

it does appear to have appreciably greater depth when compared to Paramount’s

Dolby Digital 2.0 offering. The harpsichord in the main title lullaby seems

to spike the melody rather than jangle quietly, the piano lessons heard from

a nearby apartment as the young couple look the apartment over actually sound

distant rather than muffled, the whispered chanting …, and Ruth Gordon’s

voice is that much more punishing to the ears (if producer William Castle was

going to use any gimmick to sell the film, it should have been a stereo soundtrack).

Typical

of a Paramount-licensed release, Criterion’s dual-layer Blu-Ray is coded

for Region A playback only, and it is currently the only Blu-Ray edition in

the world (but can a Paramount Region B release or two be far behind now that

Criterion has done the work on the master?). Due to the film’s pedigree,

ROSEMARY’S BABY has been fairly well-treated on DVD by Paramount (a company

that tended to dump its genre releases onto barebones disc with little digital

clean-up, prior to sublicensing several of their titles to Olive Films who continue

to dump their titles onto DVD with little restoration or extras); as such, Criterion’s

1080p MPEG-4 AVC encoding features similar 1.85:1 framing and colors to Paramount’s

2003 Region 1 NTSC DVD edition, but the new HD transfer is sharper, more detailed,

and almost looks like it could have been shot yesterday (although any recent

film attempting to capture the look of the era would probably try to degrade

the image to reflect the condition of how many of these older films look now

without restoration). Farciot Eduoart’s (VERTIGO) process shots during

Rosemary’s nightmares have always looked artificial, although some subtler

looking ones are also more obvious (notably the elevator scenes). The audio

is encoded in uncompressed LPCM single-channel mono; it may be subjective, but

it does appear to have appreciably greater depth when compared to Paramount’s

Dolby Digital 2.0 offering. The harpsichord in the main title lullaby seems

to spike the melody rather than jangle quietly, the piano lessons heard from

a nearby apartment as the young couple look the apartment over actually sound

distant rather than muffled, the whispered chanting …, and Ruth Gordon’s

voice is that much more punishing to the ears (if producer William Castle was

going to use any gimmick to sell the film, it should have been a stereo soundtrack).

As with Criterion’s other English-language releases on DVD and BD, optional English subtitles are available, but only from your remote (there is no set-up option in the menu). Besides the scene selections, Criterion’s menus also contain a bookmarking “Timeline” option, but I don’t really see much use for it (although it may be useful to some for referencing scenes since Criterion has fewer chapter marks than the Paramount DVD). The Paramount disc featured a vintage making-of featurette (23:02) that focused more on the working relationship between Polanski and Farrow through recorded comments from both played over behind the scenes footage and clips from the film. Polanski talks about his method of letting the actors run through the scene and then basing the camera coverage on their movements rather than having the actors choreograph their performances to the camera (which explains several well-shot long singe-take scenes in the finished film). Farrow says that she doesn’t think she’s flighty, but she comes off that way (the most substantive thing she has to say about her and Polanski is that “We groove together”). We also get to see Polanski’s hobby as a race car driver and Farrow’s flitting around like a free spirit, suggesting that the makers of the documentary wanted to emphasize their hippie-like qualities while also portraying them as highly creative and professional. The DVD edition also featured a retrospective featurette (16:57) featuring interviews with Robert Evans, Richard Sylbert, and Polanski.

While

the vintage featurette probably should have been retained on the Criterion disc

for the sake of posterity, the aforementioned retrospective interviews are made

almost entirely obsolete by the documentary featurette “Remembering ROSEMARY’S

BABY” (46:54) which features the participation of Evans, Polanski and

Mia Farrow. Evans describes how Castle got the option on Levin’s novel,

and how he would only greenlight it if someone other than Castle directed it

(he was impressed with Castle as a producer, but not as a director). Evans wanted

Polanski to direct the film, and got the director to read the book while in

talks with him to helm the ski film DOWNHILL RACER (Polanski was eager to direct

a film about the sport). Polanski envisioned a sexier actress for the lead and

approached Tuesday Weld (who turned it down). Jane Fonda, Julie Christie and

Joanna Pettet were also considered, but Evans pushed for Farrow (who was only

known at the time for her television work, although she was married to Frank

Sinatra at the time). In turn, Evans wanted Robert Redford for Guy (but Paramount

was suing him for pulling out of one of their films) but Polanski suggested

Cassavetes who was more believable as an Actors Studio-type (Polanski and Evans

address the director’s clashing with Cassavetes, and Evans make the observation

that if Cassavetes “took off his sneakers, he had problems with acting”).

Evans also discusses having to approach an outside advertising firm because

the studio advertising department did not know how to promote it.

While

the vintage featurette probably should have been retained on the Criterion disc

for the sake of posterity, the aforementioned retrospective interviews are made

almost entirely obsolete by the documentary featurette “Remembering ROSEMARY’S

BABY” (46:54) which features the participation of Evans, Polanski and

Mia Farrow. Evans describes how Castle got the option on Levin’s novel,

and how he would only greenlight it if someone other than Castle directed it

(he was impressed with Castle as a producer, but not as a director). Evans wanted

Polanski to direct the film, and got the director to read the book while in

talks with him to helm the ski film DOWNHILL RACER (Polanski was eager to direct

a film about the sport). Polanski envisioned a sexier actress for the lead and

approached Tuesday Weld (who turned it down). Jane Fonda, Julie Christie and

Joanna Pettet were also considered, but Evans pushed for Farrow (who was only

known at the time for her television work, although she was married to Frank

Sinatra at the time). In turn, Evans wanted Robert Redford for Guy (but Paramount

was suing him for pulling out of one of their films) but Polanski suggested

Cassavetes who was more believable as an Actors Studio-type (Polanski and Evans

address the director’s clashing with Cassavetes, and Evans make the observation

that if Cassavetes “took off his sneakers, he had problems with acting”).

Evans also discusses having to approach an outside advertising firm because

the studio advertising department did not know how to promote it.

Some of Evans’ comments on the film are repeated almost verbatim from the Paramount featurette, but that’s not such a surprise since he penned his autobiography The Kid Stays in the Picture in 1994 (it was adapted into a film in 2002). Polanski mentions getting some helpful advice from admired director Otto Preminger after clashing with Castle. Polanski admired the editing of Sam O’Steen’s THE GRADUATE, but his work on another film overlapped with ROSEMARY’S BABY (which is why O’Steen’s assistant Bob Wyman receives collaboration credit in the opening titles). Sylbert scouted The Dakota but elected to build the apartments on set because he could not find any existing locations that were suitable (we are also shown Levin’s detailed floor plan of the Castavets apartment). Farrow discusses her marriage to Frank Sinatra, who had divorce papers delivered to the set when she wouldn’t walk out on the production to co-star with him in THE DETECTIVE (Evans crows that the two films were released on the same day and ROSEMARY’S BABY was the more successful picture). She also mentions that the scene where she walks into traffic was not staged; Polanski – operating the camera himself with a pre-Panaglide/Steadicam set-up – assured her that “no one would hit a pregnant woman.” It is Farrow who makes the observation that Polanski was not satisfied with the original story because it was not ambiguous enough (perhaps this was the reason he later mounted the adaptation of THE TENANT).

Of

less interest to fans of the film is the feature-length 2012 Polish documentary

on the composer titled “Komeda, Komeda” (70:43). Although Komeda

died young (he fell and struck his head in Los Angeles, a death not unlike that

of the protagonist of Simon Hasara’s A DAY AT THE BEACH, which Polanski

began for Paramount but dropped out of after the murder of his wife), he had

made a name for himself as a jazz musician in his native Poland. The documentary

revisits the places where he recorded and performed, interviews some of his

fellow musicians, and popular musicians he has influenced. There’s very

little discussion of his film scoring, but the documentary features comments

from Andrzej Wadja and Polanski (it’s so strange to hear him speaking

Polish after years of hearing him speak accented English as an actor and on

film commentary tracks [although he did dub Zygmunt Malanowicz’s third

wheel character – a role he originally wanted to play – in KNIFE

IN THE WATER]). Oddly, neither Paramount nor Criterion could scrounge up a trailer

or a few TV spots for the film, but Criterion had included one of their comprehensive

booklets (not provided for review) that features a critical essay, Levin’s

afterward for the 2003 printing of the novel, as well as Levin’s character

sketches and apartment floor plans created in preparation for the novel.

(Eric

Cotenas)

Of

less interest to fans of the film is the feature-length 2012 Polish documentary

on the composer titled “Komeda, Komeda” (70:43). Although Komeda

died young (he fell and struck his head in Los Angeles, a death not unlike that

of the protagonist of Simon Hasara’s A DAY AT THE BEACH, which Polanski

began for Paramount but dropped out of after the murder of his wife), he had

made a name for himself as a jazz musician in his native Poland. The documentary

revisits the places where he recorded and performed, interviews some of his

fellow musicians, and popular musicians he has influenced. There’s very

little discussion of his film scoring, but the documentary features comments

from Andrzej Wadja and Polanski (it’s so strange to hear him speaking

Polish after years of hearing him speak accented English as an actor and on

film commentary tracks [although he did dub Zygmunt Malanowicz’s third

wheel character – a role he originally wanted to play – in KNIFE

IN THE WATER]). Oddly, neither Paramount nor Criterion could scrounge up a trailer

or a few TV spots for the film, but Criterion had included one of their comprehensive

booklets (not provided for review) that features a critical essay, Levin’s

afterward for the 2003 printing of the novel, as well as Levin’s character

sketches and apartment floor plans created in preparation for the novel.

(Eric

Cotenas)